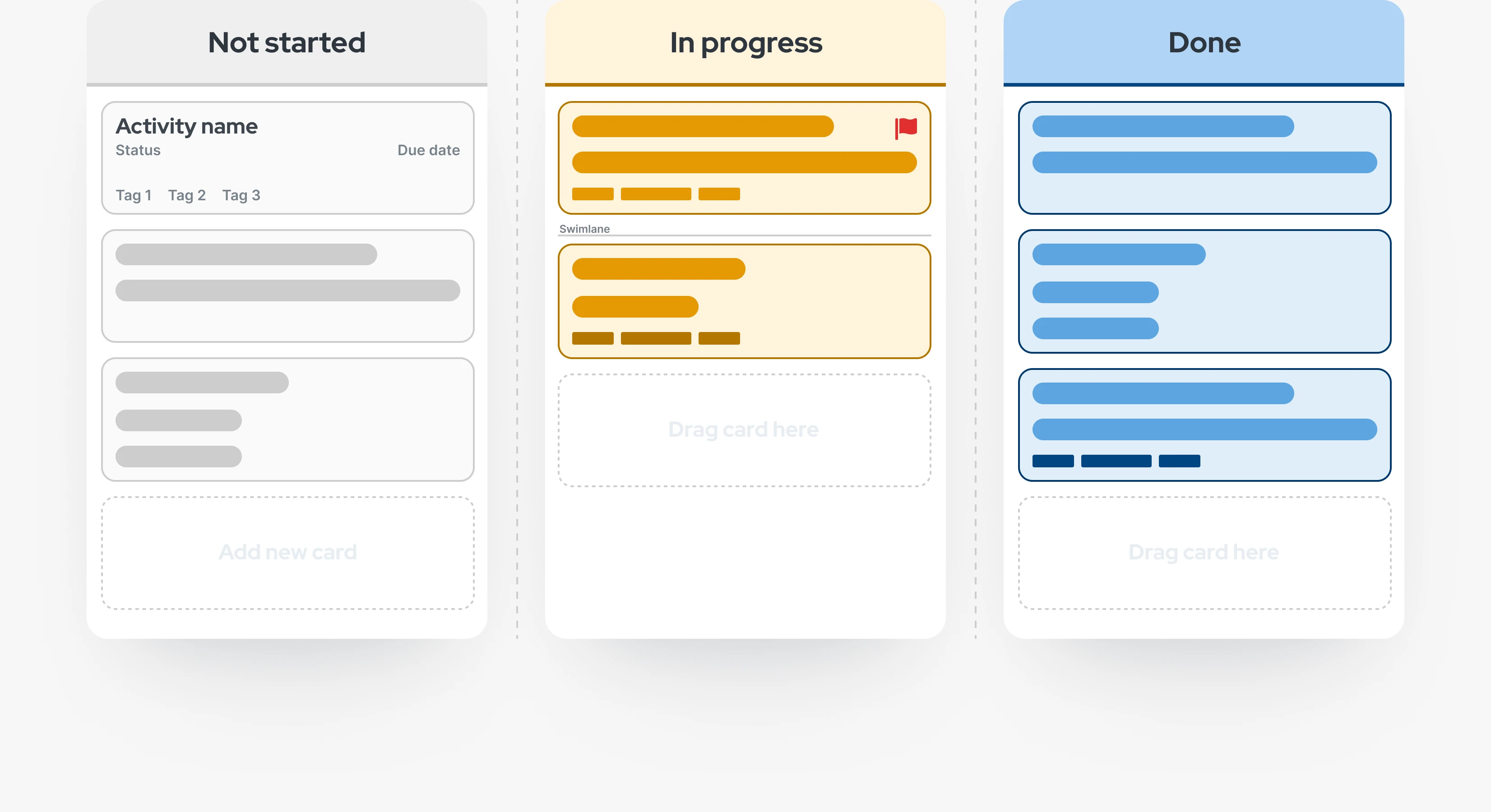

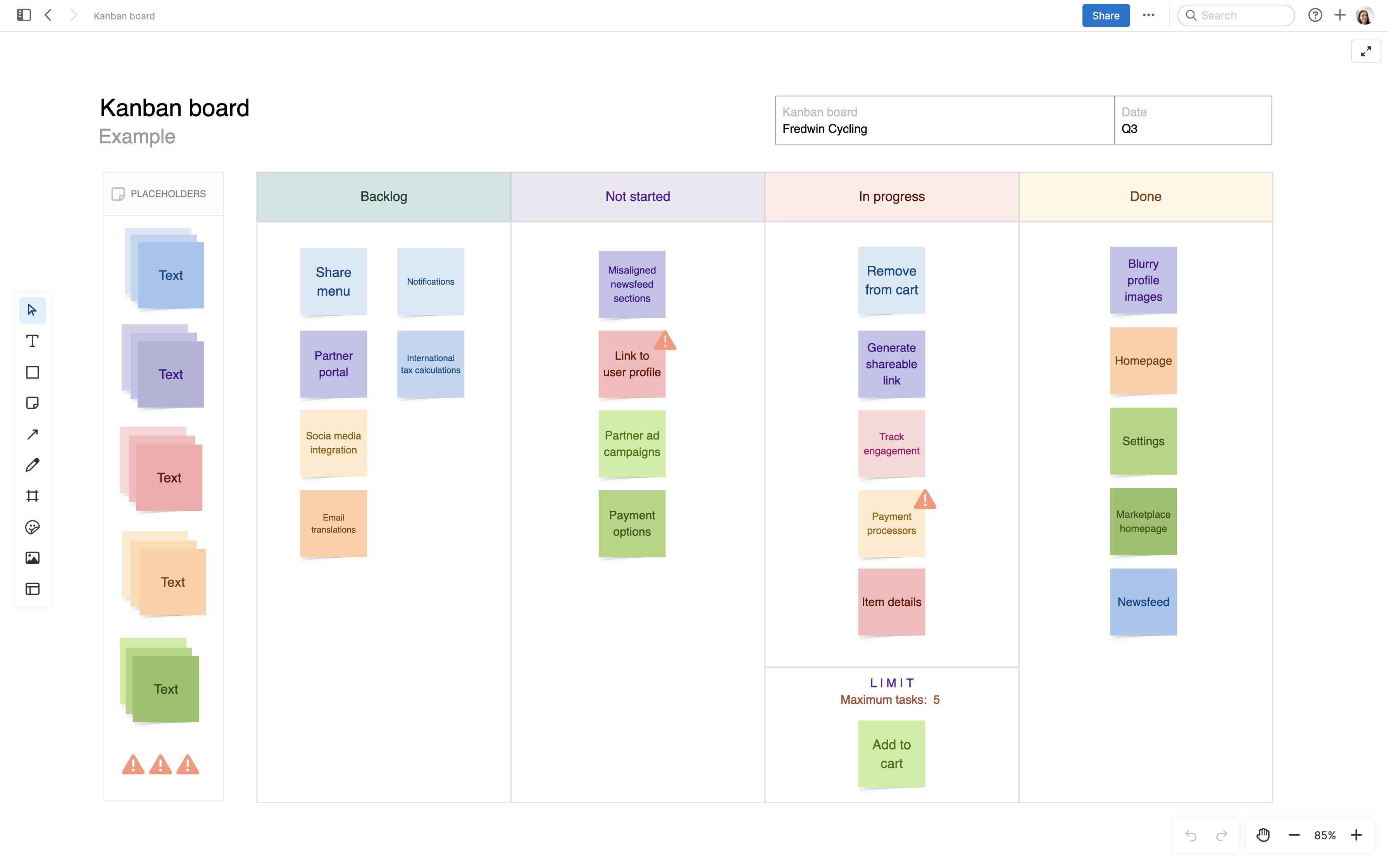

This is an example of a personalized kanban board in Aha! software.

The origins of kanban

Taiichi Ohno introduced kanban at Toyota in the mid-20th century. He was an industrial engineer and eventual executive at the company. Today, he is considered the father of the Toyota Production System, which inspired lean manufacturing in the United States.

Toyota was struggling to compete with the American car market at the time. So the company looked at how other supply chains handled fulfillment by matching inventory levels with consumption patterns — specifically studying supermarkets. Stores stocked products based on what they could sell in a given time. Customers bought what they needed since they knew they could buy more later. This led Toyota to see consumer demand as part of the manufacturing process: a required input precedent to production.

Most car manufacturers still followed Henry Ford’s method, producing a great quantity of parts that were piled beside the assembly line and used as needed. But this approach required huge amounts of upfront capital, which was challenging in post-World War II Japan. Ohno aimed to eliminate overproduction by introducing new inventory only when absolutely necessary. Factories were reorganized so that parts production and assembly happened at the same rate, with assembly workers taking parts only as needed. They called it the “just-in-time” method (JiT) — but more on that later.

Remember that supermarket research? Ohno realized that there needed to be some exchange that triggered restocking the shelves. So he introduced paper cards called kanban. Once a material was used, a kanban card would be sent back to parts production indicating to the team exactly what was used and how many more were needed to restock.

The kanban method was a significant success, evolving to support processes across many different supply chains. In short, anything that required visualization of a large volume of in-progress work could be a candidate for the new system.

Kanban in a modern context

The next evolution of kanban occurred in the early 2000s when the method was adopted as a project management tool by IT and software development teams. Many assumed lean manufacturing principles would not extend to knowledge work. But a 2004 case study of IT teams at Microsoft proved the efficacy of these concepts in managing change requests and backlogs. One of the authors of that case study, former Microsoft engineer David J. Anderson, was credited as among the first to apply kanban to software development. He went on to write many books about agile and lean methodologies. (And he even opened a kanban “university” as well as his own eponymous school of management.)

Top

Kanban principles and best practices

Again, kanban is a system and not a work philosophy. Unlike other agile frameworks, there is no list of rules and roles that must be followed to “do kanban right.” But there are some general kanban principles and best practices:

Visualize work: Visualizing work and maintaining transparency is critical to kanban. Development work is often “invisible” until it is completed. On the flip side, kanban boards make all items visible so the team can understand the details, status, and progress of everything in motion.

Limit work in progress (WIP): You can complete projects faster if you prioritize what is most important, limit how much work each person has, and focus on completion before moving on to the next item.

Manage flow: Teams that practice kanban are typically self-directing. Instead of managing the people doing the work, kanban requires careful oversight of workflows and processes so work can be completed smoothly and roadblocks can be quickly addressed.

Make process policies explicit: Clear documentation on how the team works together inspires self-sufficiency, increases shared knowledge, and improves onboarding.

Implement feedback loops: Feedback loops (also called cadences) help teams communicate with stakeholders and respond to changes in workflows and priorities. Daily team kanban meetings are one example of a feedback loop in practice. Similar to daily standups in scrum, these meetings are opportunities to discuss capacity, report on progress, and raise any concerns.

Improve collaboratively: Continual feedback and evolution are key parts of the kanban system. Positive change will always take time. Shifting too fast — and putting too many process changes in place at once — hamper a team's adoption.

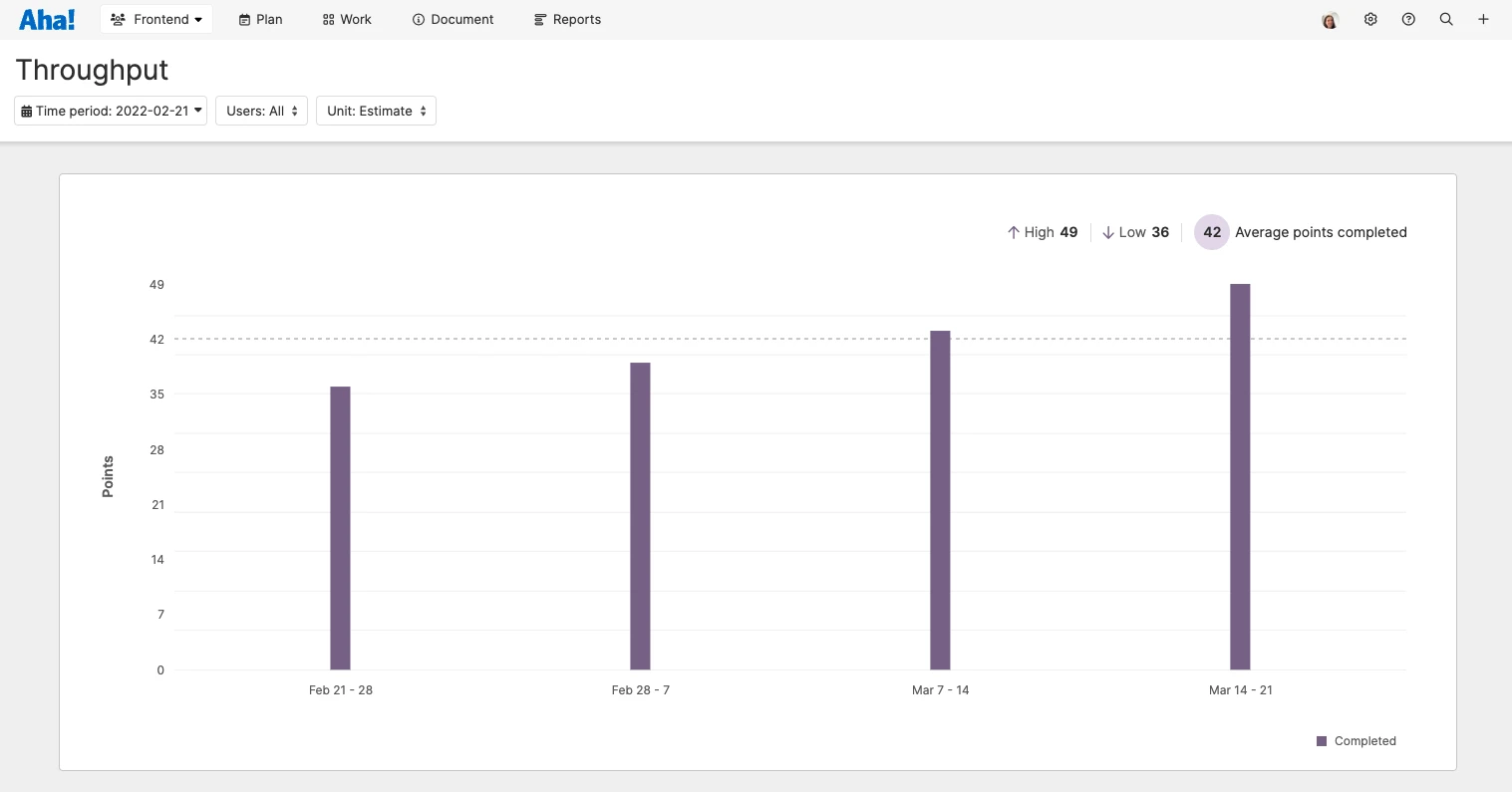

Consider metrics (without relying too heavily on them): Gauge success through goal-setting and benchmarking. Metrics such as cycle time and throughput can be a good indicator of success. (We will cover some common kanban success metrics later.)

Understand JiT: JiT puts an emphasis on delivering the simplest solution to a known issue in small releases to avoid waste (versus anticipating future unknown needs). It might not be a kanban "principle," per se, but it is definitely part of the conversation.

These principles should form the foundation of your kanban approach. Think of them as constant areas of improvement rather than as goals to achieve and check off your list.

Related:

Top

Kanban vs. scrum

The best way to recall the differences between kanban and scrum? Think: Where kanban pulls, scrum pushes. Here is a high-level comparison of the two:

| Kanban | Scrum |

Roles | There are no defined roles, but some teams have service delivery and service request managers. | Product owner, scrum master, and development team |

Release cadence | Continuous | Defined intervals called sprints (e.g., two weeks) |

Delivery | Continuous | At the end of each sprint as approved by the product owner |

Change | Change can happen at any time. | Changes should not be made to the sprint forecast during the sprint. |

Meetings | There are no defined meetings, but meetings are broken out by team level (e.g., daily standups) and service level (e.g., delivery and risk review). | There are four mandatory meetings: sprint planning, daily scrum, sprint review, and sprint retrospective. |

Performance metrics | Lead time and cycle time | Velocity and planned capacity |

Related:

Top

How to implement a kanban system

Depending on how your team currently works, implementing kanban might entail a huge shift. It has the potential to boost your team's happiness and productivity — but figuring out what works best for you takes time. Keep in mind that kanban is not right for all teams, however. (We will be the first to tell you that kanban alone is never enough for product development.) For the purposes of this guide, here is how to get started:

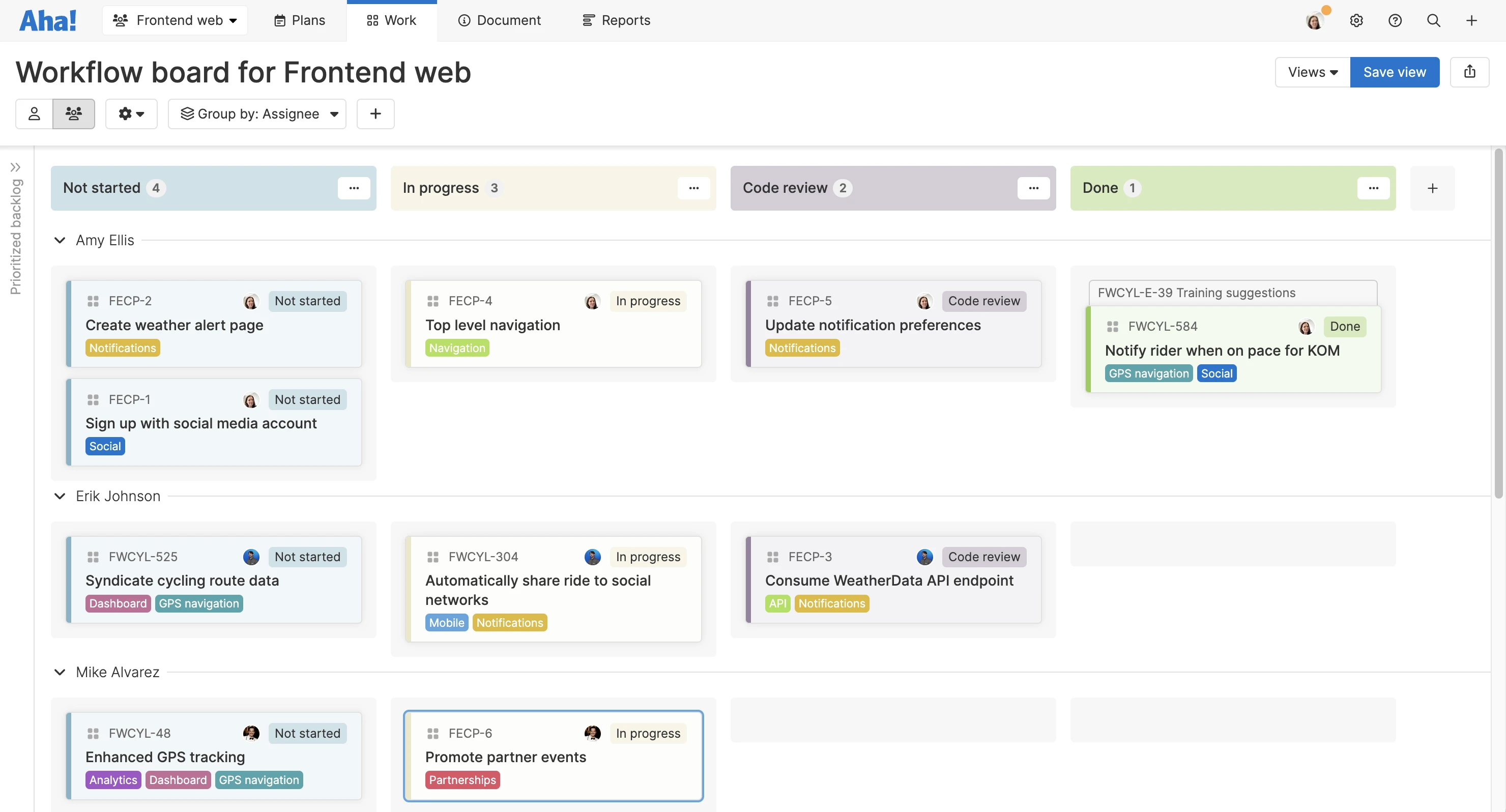

Make work visual

Set up a virtual kanban board with cards that represent work items. Carefully consider the details and layout of your cards to ensure teammates, stakeholders, and anyone in between can easily parse the work. Categorize the cards in columns — such as "Not started," "In progress," and "Done." Add as many columns as you would like, choosing names that fit your workflows.

Add details to cards as needed

You might add summaries or descriptions of the work items, their statuses, their categories or themes, the releases they belong to, and the teammates who own the tasks.

Set WIP limits

Decide on a limit for the number of cards that can exist at any time in your columns. You can always adjust this later as you get a clearer picture of how much your team can feasibly take on.

At this point, you are ready to get started, but far from done. Kanban requires continuous evaluation and tinkering. Check out our guide on how to set up a kanban board for more details.

Related:

Top

How to measure success

How do you know whether your team is truly benefiting from kanban? The answer will require looking at your progress through multiple lenses, such as feedback from the team and stakeholders as well as quantifiable data. Arguably the most important factor is whether or not you are meeting your product goals — a much bigger discussion. For now, let's look at some of the common kanban metrics teams use to evaluate performance:

Cycle time: The amount of time spent actively working on a task (or card)

Lead time: The total amount of time a task spends in your system, from initial recording through to delivery

Queues: Stages in your workflow when cards are not active, but are in a holding pattern (for example, "Waiting for review" is a common queue)

Throughput: The number of tasks or cards completed in a given time period

When will it be done: A forecast of when work will be completed based on historical data on lead times, cycle times, and throughput

WIP: Items that are in production, but not yet completed